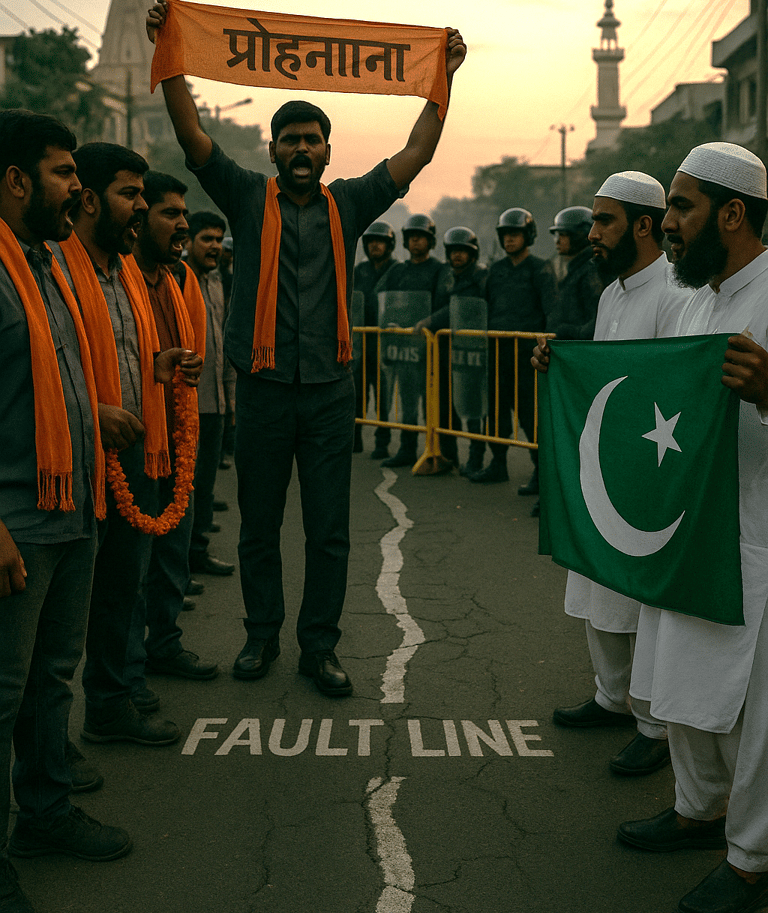

Fault Line of the Century: Hindutva vs. Islam

MIDDLE EAST

Philip Morande

10/9/20254 min read

When Samuel Huntington published The Clash of Civilizations in 1996, he argued that the defining lines of conflict in the post–Cold War world would not be ideological or economic, but cultural and civilizational. To some, it was a provocative and overly rigid thesis; to others, a self-fulfilling prophecy. But beyond its limitations, Huntington’s core idea —that deep cultural and religious identities can become vectors of geopolitical conflict— finds fertile ground today in South Asia, where India and Pakistan embody a new kind of civilizational clash.

At first glance, this tension is nothing new. India, with a territory of 3,287,263 km² and an estimated population of 1.43 billion, and Pakistan, with 881,913 km² and 241 million people, were born in 1947 amid mass religious violence and forced migrations. Their shared history has been marked by three wars, chronic territorial disputes —especially over Kashmir— and a nuclear arms race that made both countries atomic powers. But something has shifted over the past two decades: competition between the two is no longer merely geopolitical; it has become civilizational. Driven in part by their own geographic and demographic pressures, this transformation is deeply tied to the rise of Hindutva, the Hindu nationalist ideology that dominates Indian politics today, making the 687 kilometers separating Islamabad and New Delhi feel increasingly short.

Hindutva —“Hinduness”— is not merely a politicized religion. It is a redefinition of the Indian state as a Hindu civilization, where other communities, especially Muslims, are tolerated but culturally subordinated. This vision has gained strength under the leadership of Narendra Modi and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), backed ideologically and organizationally by the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). In practice, this has translated into legal reforms and historical narratives that elevate the Hindu past while questioning the place of Muslim minorities in the national identity. Nehru’s constitutional secularism has given way to a politics that presents Hinduism as the soul of the nation.

This ideological turn has direct consequences for Pakistan, a state founded precisely as a political homeland for the subcontinent’s Muslims. As India increasingly defines itself as a Hindu civilization, the clash with a state that defines itself as Islamic and nuclear is not only inevitable — it is structural. Unlike the Cold War, this is not a confrontation between abstract ideological blocs, but between two neighboring civilizations with shared borders, violent memories, and powerful armies.

Tensions are further amplified by India’s internal dynamics. With over 200 million Muslims, India hosts the second-largest Muslim population in the world. In this context, Hindutva politics has both an external dimension —Pakistan as a civilizational “other”— and an internal one: redefining what it means to be Indian in the 21st century. Developments in Kashmir, citizenship reforms that discriminate against Muslims, and official rhetoric about “disloyal elements” have consolidated a climate in which Muslim identity is perceived simultaneously as an internal and external threat.

Pakistan watches this process closely — but also sees opportunities. As India adopts a more explicitly civilizational discourse, Islamabad strengthens its role as a regional Islamic pole, tightening its ties with Saudi Arabia and tacitly benefiting from a shared nuclear umbrella that boosts its deterrence against New Delhi. Its alignment with Riyadh also expands its geopolitical reach: Pakistan is no longer just India’s eternal rival, but a player embedded in a wider axis linking the Gulf, Central Asia, and China.

This ideological and geopolitical context creates a particularly volatile environment. Unlike civilizational clashes “at a distance” —such as that between the West and the Islamic world— here we have two adjacent civilizational poles, with long land borders, intertwined populations, and ready nuclear arsenals. Hindu nationalism is not just an internal phenomenon: it projects outward a vision of India as a civilizational power facing a rival Muslim sphere. Pakistan, for its part, responds from an Islamic identity inseparable from both its founding rationale and its strategic role in the Muslim world.

China adds another layer to this dynamic. Officially secular, Beijing maintains deep tensions with its Muslim minorities, particularly the Uighurs, and monitors any Islamist alignments in Central or South Asia that could affect its strategic corridors. At the same time, it sees in Pakistan a key partner for the Belt and Road Initiative, and in India a direct geopolitical competitor. The civilizational rivalry between India and Pakistan unfolds within a broader strategic board involving China, the Gulf, and even Russia.

Huntington’s framework, therefore, deserves reinterpretation. This is not a global “clash of civilizations” between monolithic blocs, but a localized yet deeply structural fracture, where religious identities shape power politics. India is no longer merely a rising secular state; it is a civilization in self-assertion. Pakistan is not simply a weak Islamic state; it is a strategic pivot with relevant allies and nuclear capabilities. And the fault line between them runs not only along their borders but also through their societies.

Ultimately, the danger is not only the prospect of open war —though that risk is ever-present between nuclear powers— but that this ideological–cultural rivalry reshapes alliances and tensions across South Asia. If Hindutva continues to shape Indian politics and Pakistan remains anchored in its Islamic identity and regional alliances, the Indo–Pakistani border could become one of the key civilizational fault lines of the 21st century, gradually shifting the geopolitical focus from the Middle East to the subcontinent. Is the Middle East, then, projecting itself onto another part of the world, displacing the West’s role as the great global intervener? That will be the subject of another column.